|

| The first book of Freakonomics series |

Incentives are the cornerstone of modern life. And understanding them — or, often, ferreting them out — is the key to solving just about any riddle, from violent crime to sports cheating to online dating.

We all learn to respond to incentives, negative and positive, from the outset of life. An incentive is simply a means of urging people to do more of a good thing and less of a bad thing. But most incentives don’t come about organically. Someone — an economist or a politician or a parent — has to invent them.

There are three basic flavors of incentive: economic, social, and moral. Very often a single incentive scheme will include all three varieties. Think about the anti-smoking campaign of recent years. The addition of a $3-per-pack “sin tax” is a strong economic incentive against buying cigarettes. The banning of cigarettes in restaurants and bars is a powerful social incentive. And when the U.S. government asserts that terrorists raise money by selling black-market cigarettes, that acts as a rather jarring moral incentive.

Whatever the incentive, whatever the situation, dishonest people will try to gain an advantage by whatever means necessary. For every incentive has its dark side. A thing worth having is a thing worth cheating for. For every clever person who goes to the trouble of creating an incentive scheme, there is an army of people, clever and otherwise, who will inevitably spend even more time trying to beat it.

|

| Mimi and Eunice : Incentive to Create |

The conventional wisdom is often wrong. Crime didn’t keep soaring in the 1990s, money alone doesn’t win elections, and — surprise — drinking eight glasses of water a day has never actually been shown to do a thing for your health. Conventional wisdom is often shoddily formed and devilishly difficult to see through, but it can be done.

The first trick of asking questions is to determine if your question is a good one. Just because a question has never been asked does not make it good. Smart people have been asking questions for quite a few centuries now, so many of the questions that haven’t been asked are bound to yield uninteresting answers. But if you can question something that people really care about and find an answer that may surprise them — that is, if you can overturn the conventional wisdom — then you may have some luck.

|

| Dilbert : Monday, June 9, 1997 |

Dramatic effects often have distant, even subtle, causes. The answer to a given riddle is not always right in front of you.

Perhaps the most dramatic effect of legalized abortion was its impact on crime. In the early 1990s, just as the first cohort of children born after Roe v. Wade was hitting its late teen years — the years during which young men enter their criminal prime — the rate of crime began to fall. What this cohort was missing, of course, were the children who stood the greatest chance of becoming criminals. And the crime rate continued to fall as an entire generation came of age minus the children whose mothers had not wanted to bring a child into the world. Legalized abortion led to less unwantedness; unwantedness leads to high crime; legalized abortion, therefore, led to less crime.

We have evolved with a tendency to link causality to things we can touch or feel, not to some distant or difficult phenomenon. It may be more comforting to believe what the newspapers say, that the drop in crime was due to brilliant policing and clever gun control and a surging economy. We believe especially in near-term causes: a snake bites your friend, he screams with pain, and he dies. The snakebite, you conclude, must have killed him. Most of the time, such a reckoning is correct. But when it comes to cause and effect, there is often a trap in such open-and-shut thinking. We smirk now when we think of ancient cultures that embraced faulty causes—the warriors who believed, for instance, that it was their raping of a virgin that brought them victory on the battlefield. But we too embrace faulty causes, usually at the urging of an expert proclaiming a truth in which he has a vested interest.

|

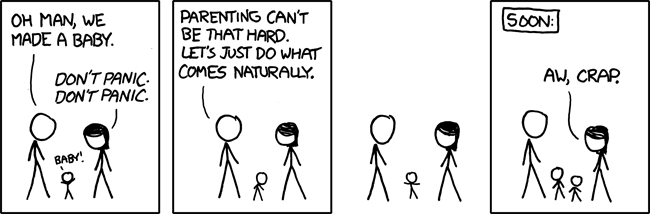

| xkcd 674 : Natural Parenting |

“Experts” use their informational advantage to serve their own agenda. However, they can be beat at their own game. And in the face of the Internet, their informational advantage is shrinking every day — as evidenced by, among other things, the falling price of coffins and life-insurance premiums.

Information is so powerful that the assumption of information, even if the information does not actually exist, can have a sobering effect. The gulf between the information we publicly proclaim and the information we know to be true is often vast. (Or, put a more familiar way: we say one thing and do another.) This can be seen in personal relationships, in commercial transactions, and of course in politics.

An expert must be bold if he hopes to alchemize his homespun theory into conventional wisdom. His best chance of doing so is to engage the public’s emotions, for emotion is the enemy of rational argument. And as emotions go, one of them—fear—is more potent than the rest.

No one is more susceptible to an expert’s fearmongering than a parent. Fear is in fact a major component of the act of parenting. The problem is that they are often scared of the wrong things. When hazard is high and outrage is low, people underreact, and when hazard is low and outrage is high, they overreact.

By the time most people pick up a parenting book, it is far too late. It isn’t so much a matter of what you do as a parent; it’s who you are. Parents who are well educated, successful, and healthy tend to have children who test well in school.

The eight ECLS factors that are correlated with school test scores:

- The child has highly educated parents.

- The child’s parents have high socioeconomic status.

- The child’s mother was thirty or older at the time of her first child’s birth.

- The child had low birthweight.

- The child’s parents speak English in the home.

- The child is adopted.

- The child’s parents are involved in the PTA.

- The child has many books in his home.

The eight factors that are not:

- The child’s family is intact.

- The child’s parents recently moved into a better neighborhood.

- The child’s mother didn’t work between birth and kindergarten.

- The child attended Head Start.

- The child’s parents regularly take him to museums.

- The child is regularly spanked.

- The child frequently watches television.

- The child’s parents read to him nearly every day.

Correlation does not equal causality. When two things travel together, it is tempting to assume that one causes the other. Married people, for instance, are demonstrably happier than single people; does this mean that marriage causes happiness? Not necessarily. The data suggest that happy people are more likely to get married in the first place. As one researcher memorably put it, “If you’re grumpy, who the hell wants to marry you?"

|

| xkcd 552 : Correlation doesn't imply causation. |

Knowing what to measure and how to measure it makes a complicated world much less so. If you learn how to look at data in the right way, you can explain riddles that otherwise might have seemed impossible. Because there is nothing like the sheer power of numbers to scrub away layers of confusion and contradiction.

_____

The three hardest words in the English language is "I don't know." In most cases, the cost of saying “I don’t know” is higher than the cost of being wrong—at least for the individual. Every time we pretend to know something, we are doing the same: protecting our own reputation rather than promoting the collective good. None of us want to look stupid, or at least overmatched, by admitting we don’t know an answer. The incentives to fake it are simply too strong, so many people are willing to predict the future. A huge payoff awaits anyone who makes a big and bold prediction that happens to come true. If you say the stock market will triple within twelve months and it actually does, you will be celebrated for years (and paid well for future predictions). What happens if the market crashes instead? No worries. Your prediction will already be forgotten. Since almost no one has a strong incentive to keep track of everyone else’s bad predictions, it costs almost nothing to pretend you know what will happen in the future.

No comments :

Post a Comment